Assessments at Scale

Lightning Talk at the Tech4Impact Non-Profit Convergence hosted by Dasra & Project Tech4Dev.

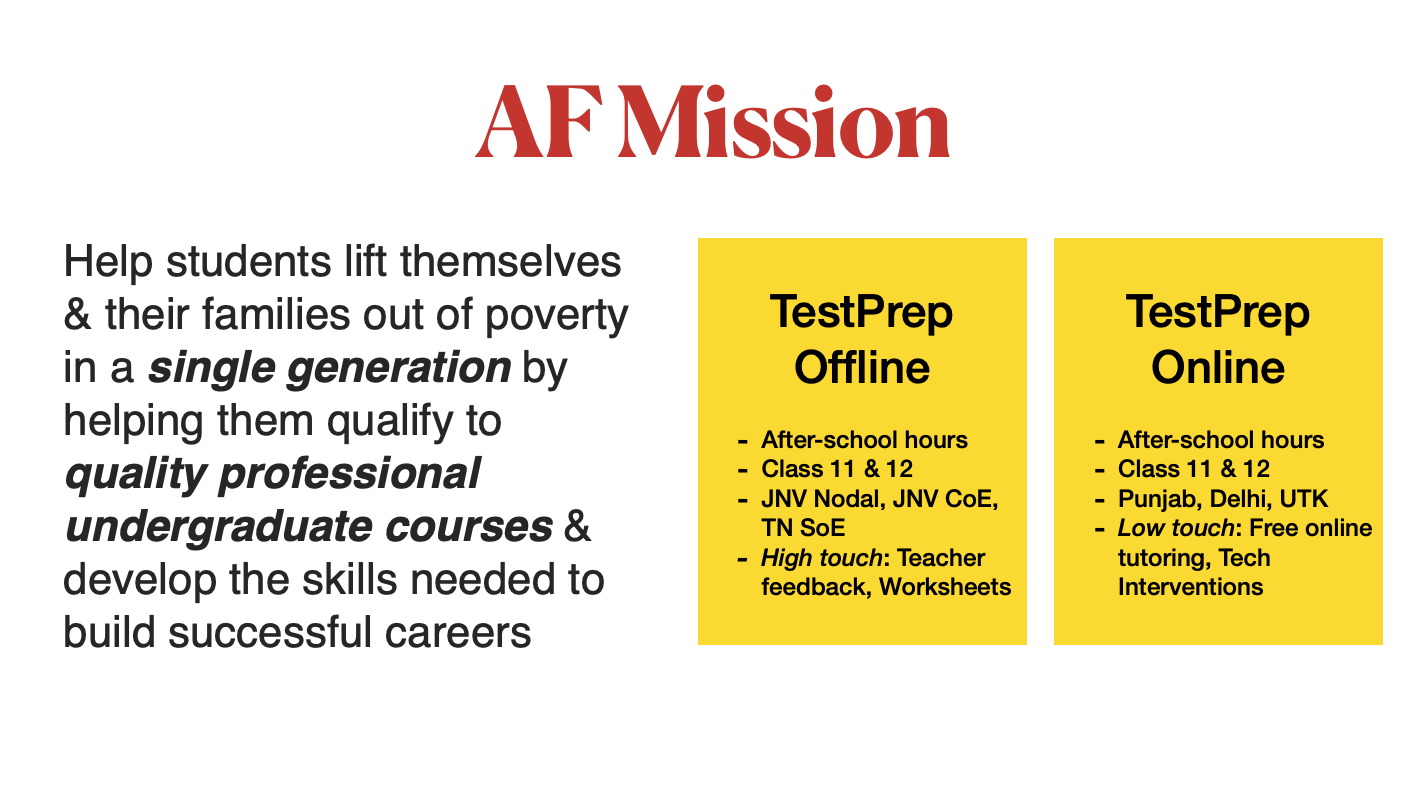

Context: The annual Tech4Impact event brings together leaders of several NGOs to exhange ideas on technology in social sector. I spoke briefly about the assessments we conduct and the role that tech plays in making them work at scale. The aim was to spark reflection on how we position tech for impact. Slides are available here.A quick overview of what Avanti does: we undertake a combination of free offline and digital interventions to enhance educational outcomes in India. In particular, we focus on underserved grade 11 and grade 12 students in government schools, helping them excel in competitive exams like JEE and NEET. The idea is that by entering top colleges and landing well-paying jobs, these students can lift their families out of poverty.

Our main program, Testprep, runs in two forms. The offline model places teachers in schools, offering high-touch support — from tutoring in after-school hours to detailed individual feedback. As expected, this is costly for us and not easy to scale. The online model delivers free classes on Google Meet, which is cheaper and far more scalable, but with lower impact.

And here, tech naturally occupies centre stage; it’s the piece that seems to make scale possible.

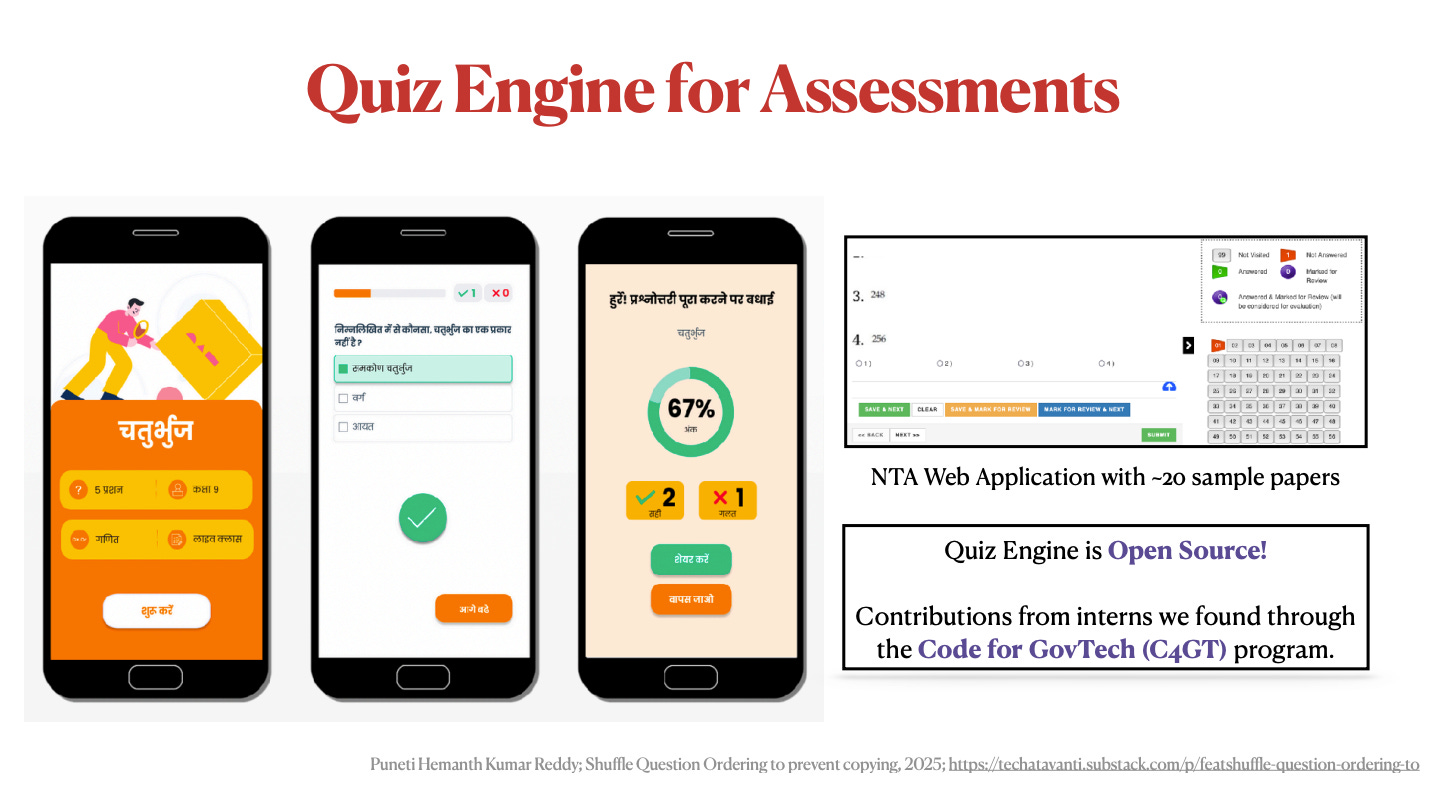

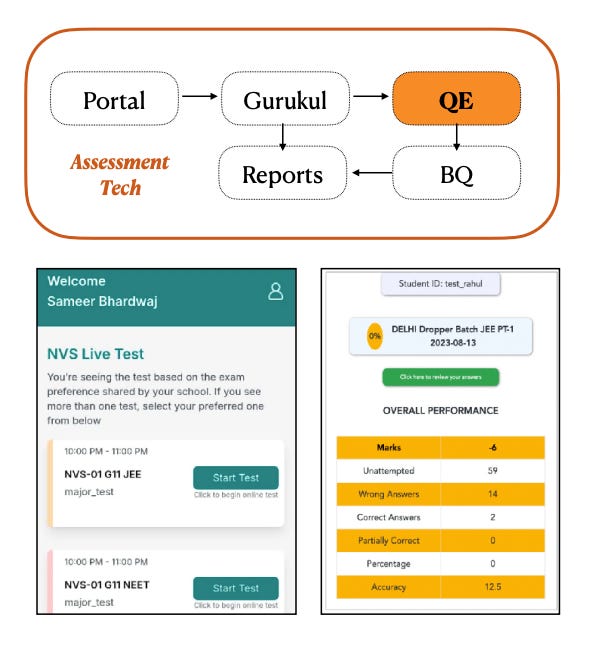

One of our key digital tools for TestPrep is the Quiz Engine. It’s designed to mimic the National Testing Agency's (NTA) online exam environment, giving students a realistic training ground for their final exams.

Like all our tech, we’ve kept it open-source, and that’s been a big plus. For example, through the Code for GovTech program, we received a neat contribution that randomizes question order to cut down cheating.

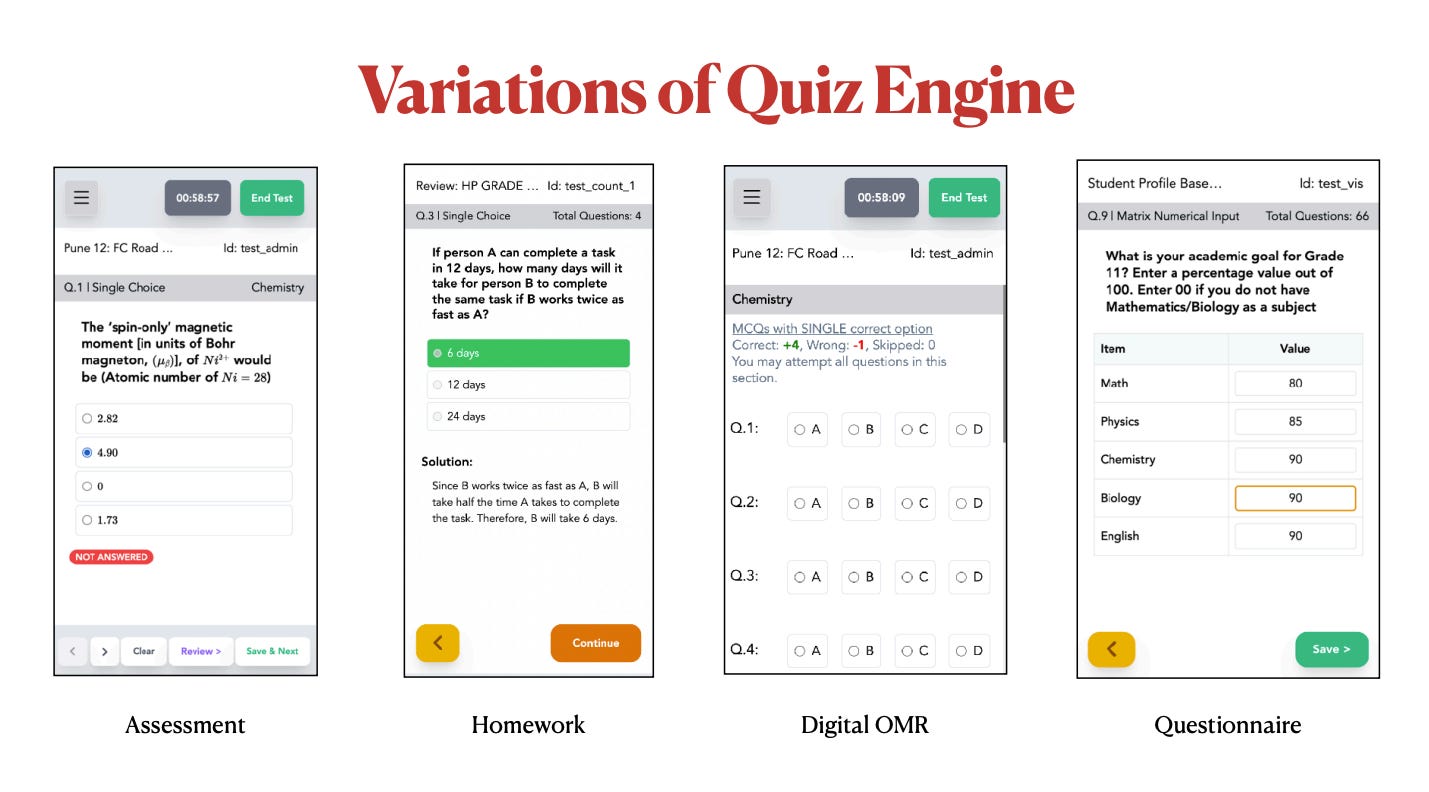

Beyond assessments, the Quiz Engine also has a few other variations.

Homework mode is deliberately low-stakes: it has no timer, so students can slow down, focus on practice, and build conceptual clarity.

OMR mode works well in schools with poor internet. Students solve on paper and then just key in their answers, like bubbling an OMR sheet. Since there’s no need to load text or images, this screen comes up super fast.

And finally, a questionnaire mode, which we use for post-quiz surveys and feedback.

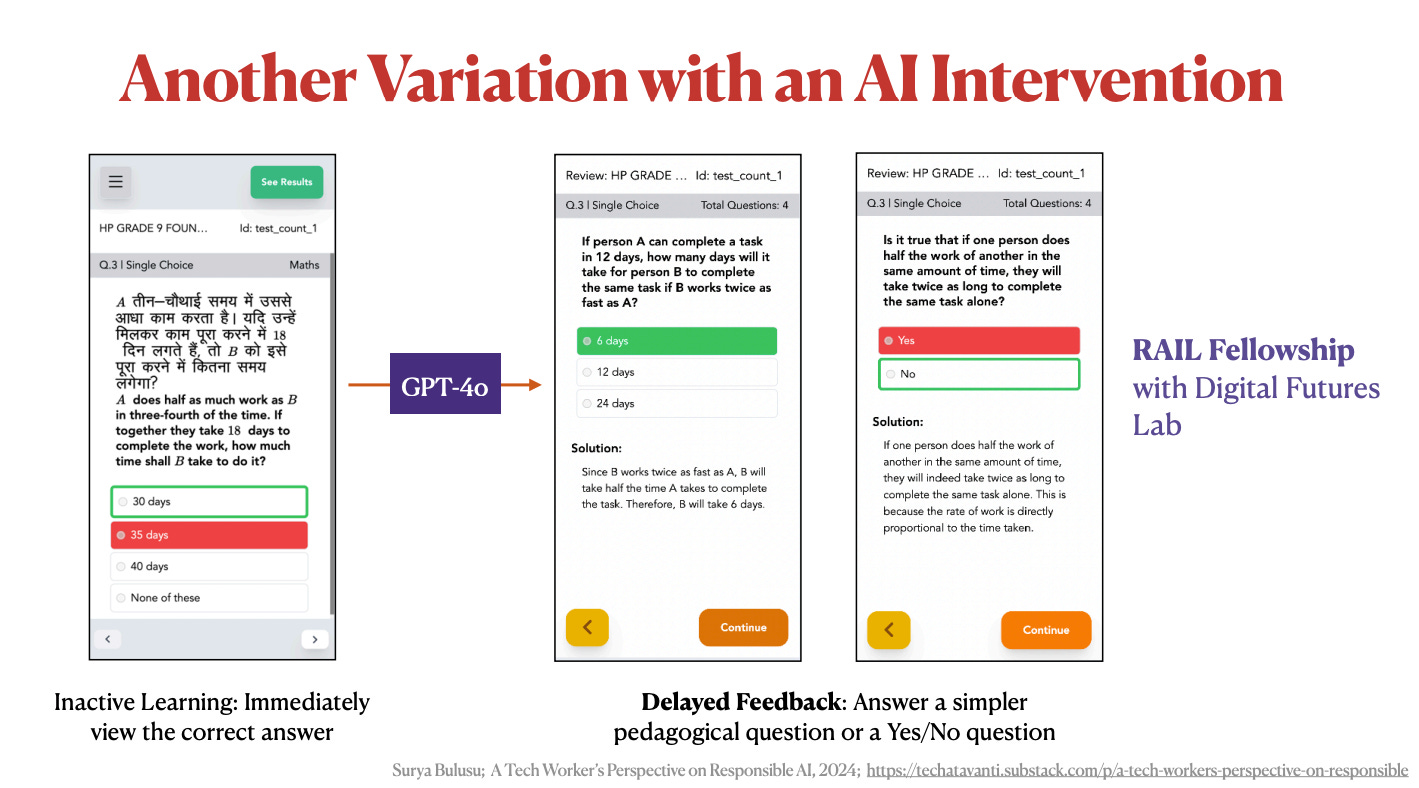

We also tried an AI intervention. The problem is that students rarely revisit the questions they got wrong. So we used an LLM to generate review quizzes — with small fill-in-the-blanks or yes/no questions — to make revision quicker and more engaging.

We developed this during the Responsible AI Fellowship with Digital Futures Lab, and it certainly helped us view the tool from a teacher’s perspective and refine the interface. It’s still experimental, mainly because we’re struggling to design strong feedback loops that improve the prompts.

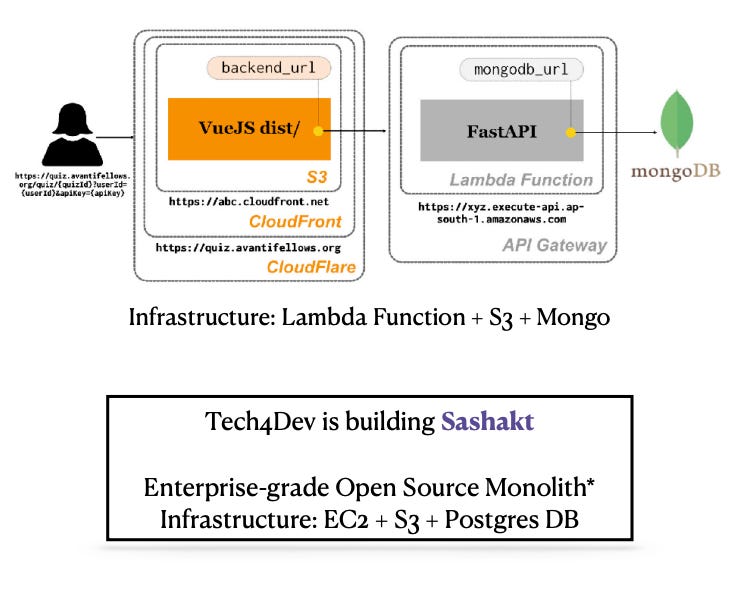

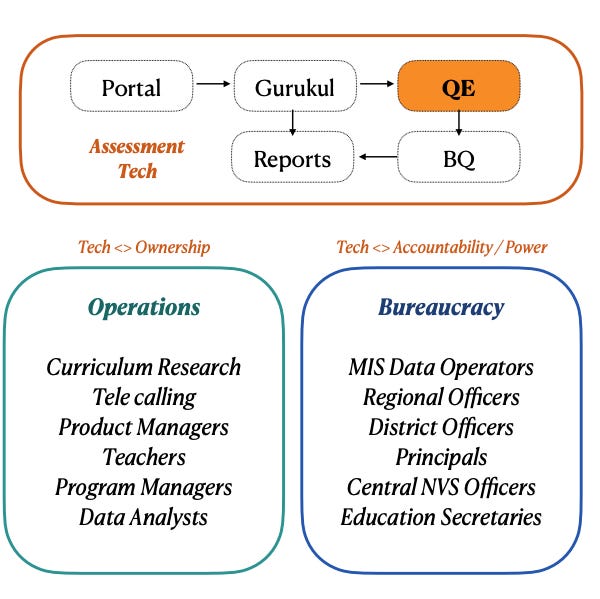

QE: A Simple Microservice

I’ll briefly touch on the technical details. The quiz engine is only one piece of our assessment tech. Students log in through the Portal service, land on Gurukul, pick a test, and from there enter the quiz. They can view their report cards back on Gurukul once the test is over. For assessments to scale, every part of this flow has to scale smoothly; otherwise, one bottleneck brings everything down.

The infrastructure behind this is simple: a FastAPI backend on Lambda, and a static frontend on S3. At the risk of sounding smug, I think good software design should feel this way — so straightforward and boring that there isn’t much to describe. Of course, there’s room for improvement. A relational database could speed up queries. The backend could run on EC2, and so on.

Moreover, the engine itself in isolation might not always work for other organizations. So, Tech4Dev is already experimenting with a more enterprise-grade monolithic version that brings all of this together, called Sashakt. To me, that’s the strength of keeping code open: others can build on top of our work and create something more widely useful.

NVS Assessment: A Recent Example

The microservice structure indeed works quite well for us. Last year, we handled five lakh test attempts, and in the first week of September alone, we saw up to fifty thousand attempts. This surge followed an MoU with Navodaya Samiti to conduct system-wide assessments.

To put it in perspective, there are roughly 650 JNVs or Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas in India, at least one per district. If each has about 100 students — 50 in grade 11 and 50 in grade 12 — that’s around sixty-five thousand students. We registered sixty thousand, and fifty thousand attempted the first test last week. The slight mismatch is due to floods in some northern states and lower turnout in Lucknow and Patna regions. Overall, our tech held up well, barring a few network-related complaints.1

To be sure, the numbers still fall short of NTA’s JEE Mains intake, which amounts to a total of fifteen lakh test attempts. And much (much!) shorter than the lofty numbers Big Tech cites — of reaching the next billion users.2

But with our limited resources, it’s more important to focus on the right set of students, like the NVS system does, reaching nearly all of them and consistently improving outcomes. This turns out to be more crucial for impact than chasing sheer scale.3

Did we achieve this scale solely through tech?

I’m sure it is acknowledged in this room, but it’s worth reiterating that tech, especially in the NGO space, doesn’t achieve much on its own.

Let me give you concrete examples through this NVS assessment. Over the years, our Operations team built trust with teachers and principals across JNVs. This didn’t come easily — program managers visited multiple regional offices, helped with alumni data collection, conducted webinars, and patiently explained our tech. Even secretaries in the central NVS office showed interest and faith in our effort.

Tech did help — it gave operations confidence and ownership. Dashboards let them respond to students’ grievances directly. The UI has been malleable enough that they can tweak it themselves.4

A takeaway from this experience is about prioritization. Suppose I have two tasks: to migrate a backend service to Go (compiled language, faster), or build something that eases operations work. With limited time, I’ll probably lean toward the second, as it generally tends to have a bigger impact.

There are risks if we accept every request uncritically, because it results in bloat. Microservice architecture really helps here: the portal usually absorbs most of the bloat, keeping the quiz engine relatively pristine.

So, tech clearly isn’t the sole driver, but can we call it the most important or emblematic aspect?

Again, I don’t think so. From my experience, the most underrated instrument for scale is paper — notices, diktats, circulars — that proponents of digitization like us often mock. It’s astonishing how powerful and pervasive they are.

A central office floats a notice PDF on WhatsApp. Regional officers print it, sign it, scan it, and send it to principals. Principals download it, sign it again, and stick it on their notice board. Then, to further deepen accountability, someone clicks a photo of that notice board, shares it back, and eventually it lands in a final report.

It’s kind of absurd, patronizing, and even authoritative. But the point is: it works. It gets the country’s schools on board with surprising speed. And if you’re curious, there’s an amusing academic paper about its affordances by Akash Solanki, which I’ve referenced here.

Final Remarks

To summarize, our assessment tech is simple, both in its function and infrastructure. Collaborations with the open source and wider NGO community have been invaluable in improving it.

Is tech the driver for scale? My sense is that tech is necessary, but never sufficient. Operational muscle and bureaucratic willingness justifiably play a larger role.

This isn’t to downplay tech — I’m a tech worker myself and I’d like to keep my job and thrive in it — but to highlight where it can shine most, and complement the efforts of operations.5

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Thomas Mampilly for providing feedback on earlier iterations of the talk.

If you spot any errors, have suggestions for improvements, or wish to contribute to our repositories, please reach out to us on Avanti’s Discord channel: https://discord.gg/fjNK6ZEt

References

Sean Goedecke, Everything I know about good software design. https://www.seangoedecke.com/good-system-design/

Jennifer Pahlka, Recoding America: Why government is failing in the digital age and how we can do better. Metropolitan Books, 2023.

Aakash Solanki, Untidy Data: Spreadsheet Practices in the Indian Bureaucracy, Lives Of Data, Institute of Network Cultures 2020.

With the current stack, we can scale to more students. Maybe include grade 10 students of JNVs, or collaborate with the Tamil Nadu government to reach more than ten lakh grade 11 and grade 12 students in their schools.

This is not intended to be dismissive of Big Tech’s ambitions. If anything, we learn from them and hope to inculcate some of their values. Still, it’s worth reflecting on the differences between NGO-led tech and Big Tech.

I discussed this line of thought with Rajasekhar Kaliki of Piramal Foundation. In his long and successful stint at Google, he observed several products that failed to take off (Duo, Loon, Hangouts), yet he found the graveyard of NGO Tech (forms, chatbots, dashboards) strikingly worse. Is there something inherently more challenging about the tech we build?

Jennifer Pahlka’s book Recoding America touches on this, though her focus is largely on perverse accountability in GovTech contexts. In a future post, I hope to explore whether NGO tech is truly unique, and if so, whether it ends up bending the conventional ideas of good software design.

Discussions on impact versus scale surfaced repeatedly during the event. Prominently, Gaurav Arora of Salaam Bombay Foundation voiced it.

Many improvements in the quiz engine, like the digital OMR or the subset pattern trick to fetch questions on the fly, came directly from their feedback.

Some people jokingly pointed out that my remarks suggested tech workers feeling sidelined in NGOs. That wasn’t my intention at all! But I see the merits of their interpretation in hindsight.

This also came up in a group discussion on hiring and retaining tech talent. Sapna Karim from Janaagraha noted that one challenge is tech workers getting bored, and she suggested keeping space for innovative (greenfield) projects as a way to address it. I think that’s a useful step, but more of a stopgap solution. I hope to list possible alternatives in a future post.